Commissioning an original work of art for a religious community can be a faith-filled journey resulting in an important and meaningful acquisition. The process can help to define values and priorities, manifesting them in a physical representation that will be treasured as a legacy by future generations. But how does a faith community begin and navigate the journey which is, necessarily, to an unknown destination? It begins, as do all great expeditions, with long discussions and careful planning.

Soul Food

Why should a faith community spend any of its time or treasure on art? Why not simply gather for worship in a simple building and spend the surplus budget on a soup kitchen and other good works? Simply because good design and art work nourishes the soul and offers a glimpse of the glorious.

When we create, we emulate and honor God, acknowledging and appreciating the value of the beauty of His creation. Although there are denominations which shun certain forms of artwork, all religions make design decisions: their building’s architecture, interior layout, colors, decoration (or lack thereof), and proportions all make a statement about their faith and style of worship.

If our religion teaches us that each soul is precious and unique and yearns for something beyond ourselves and our daily existence, what better way to convey this message, to convert the nonbelievers and to sustain the believers, than to lift up the beautiful and the unique in contrast to the necessary and the mundane? There are neighborhoods, whether impoverished or simply uninspired, where the churches are the only place that residents –and their children– will experience true art, noble materials, and beautifully designed and crafted works. Houses of worship can be the galleries in the ghettoes, the creative in the midst of the commercialized, the meticulously crafted juxtaposed to the mass produced.

The way in which a parish discusses these concepts begins the journey to commissioning an appropriate and enduring work of art for its worship space.

Function & Form

Function & Form

Having determined that artwork would be beneficial in a religious environment, the next step is to determine its purpose. Should it be... Invitational? Welcoming? Awe inspiring? Devotional? Meditative? Mood setting? How about permanent or seasonal? A focal point or a backdrop?

The answers to these questions will provide guidance for determining proper location, size, and finish of the piece: exterior or interior; diminutive, life size, or monumental; monotone, muted, full color, or gilded. Likewise, various options for material and installation will be considered or eliminated: bronze, fiberglass, plaster, wood, stone, glass, tiles, textiles, metals, etc.; stationary or moveable, eye level or elevated; spotlighted or backlit, and so on...

Consultants & Committees

Now it is time to call in the professionals. And the volunteers. Today it is a rare, if anachronistic, pastor or patron who directs an ecclesiastical art project alone. The services of professionals and the input of members of the parish provide insurance against the hiring of amateurs and the creation of shrines to personal tastes.

Although generally not skilled in the hands-on application of the fine arts and crafts themselves, architects and liturgical consultants can be a helpful resource for understanding materials, processes, and proportion, as well as how to integrate art and decoration into the environment and the liturgy. Just as important as their knowledge of products is their familiarity with producers: they have built networks of artisans whose skill and professionalism they have vetted, assuring quality and reliability. Finally, if an art commission is part of a larger construction or renovation project, the architect or design consultant should bring the ability –and be given the authority– to oversee the schedules of contractors and artisans so that all elements of the project are coordinated and installed in a logical and timely fashion.

While pastors and professionals bring necessary education and experience to the project, they must never forget that they are stewards of the faithful’s donations. Not only are the members of the flock asked to contribute their money to the cause, some are called to donate their time and expertise as well. After the professionals have moved on to their next commissions and assignments, these volunteers and their families and neighbors are the ‘end users’ of the completed project. Thus, the volunteer committee plays an important role in the process.

Ironically, faith communities may differ greatly from one another in their theology but they tend to establish remarkably similar committees regarding the art and architecture of their worship facilities. Availability will dictate that a majority of committee members will be retired; practicality will draw people from related backgrounds in construction, interior design, religious education, fundraising; passion will motivate a few unlikely volunteers who will bring an extra layer of perspective and personality to the process. And somehow, these disparate individuals become a cohesive group that is a microcosm of the congregation with its best interests at heart, and manage (in spite of some minor bickering) to find and commission an artist to create something lovely and lasting.

Finding an Artist

Many factors have contributed to fewer artists working in the religious field: the closure and consolidation of traditional churches, the growth of austere mega-churches, increased options for commercial and residential applications of architectural and decorative arts, the lure of better paying and cleaner computer artwork as opposed to hands-on crafts. So, where are the remaining liturgical artists and how does a parish find them?

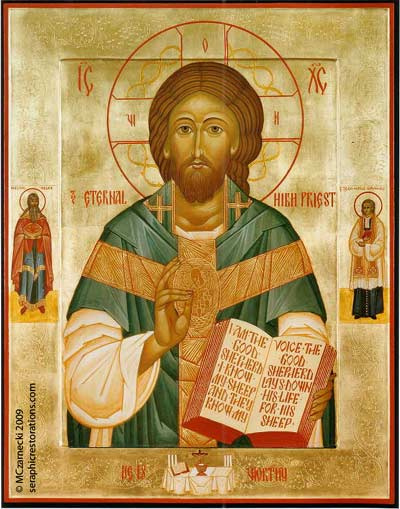

The consensus among religious artists is that while brochures, websites, and advertising may reinforce one’s standing as a professional, nothing compares to the recommendation of a former client in making a connection with a potential client. In a larger context, this can include publicity for work commissioned by a high profile client or institution. Iconographer Marek Czarnecki received many national inquiries and commissions after allowing the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops to use one of his icons as the promotional image of the Year for Priests. Such commissions offer publicity to the artist and an imprimatur to the buyer in this niche market.

In addition to articles, and their consultants’ rolodexes, pastors and committees generally look to other religious buildings for examples of good work and references for artists. Calls and visits are made to nearby churches and temples, and committee members will find themselves looking more critically at worship facilities they visit while on vacation or business trips. Denominational and local ecumenical resources can include databases of artisans and exhibit opportunities for them at clergy gatherings.

After reviewing images and references, one or more artists are contacted about the potential project and invited to meet with the committee to show a portfolio and to discuss the possibilities for a commission. While an artist must show a level of competence and an appropriate style, it is impossible to show the final product the client is seeking. Thus, offering one’s talent and skill for hire requires as much silence as speaking and as many questions as answers. In addition to being interviewed, the artist should interview the client as well, in order to learn about the parish’s mission, tradition, and vision. This dialogue will provide clarity to both practitioner and patron as to whether this collaboration would be a happy and productive one.

The Leap of Faith

The Leap of Faith

At some point, the committee must choose one artist or studio for the project. This decision is based on an assessment of artistic factors including medium, style, vision, and ability; practical concerns regarding references, cost, schedule availability are weighed; and personality plays a role as in any hire. Meanwhile, the same considerations are being weighed by the artist: Can I work with the setting? Do they want what I offer? Can I interpret their vision? Will they pay on time? Will they pay enough? Is their deadline realistic? How many committee meetings will they expect me to attend? Will they try to micromanage the project or give me some artistic license?

It is a leap of faith for both parties as they begin the hands-on process of creating a unique work of art. Fr. John Valencheck, a Catholic priest who has commissioned a number of paintings for his parish in Cleveland notes that "there is a certain amount of risk commissioning an original piece of art. You might be able to return a mass produced statue or chalice; not so something that took months of a man’s life to produce to your specifications." He offers some practical advice while in pursuit of the precious: "It is important to know your budget right up front. Have a size and timeline, and basic theme in mind." He also encourages the patron to give clear guidelines regarding important attributes and elements of the work, and the artist to submit preliminary sketches for review. Then, he suggests the patron step back and trust the artist, cautioning that "if you want a paint-by-numbers painting from your head, don’t expect a priceless work of art."

Indeed, if the average worshipers could create their own works of art, they would. Unfortunately, some try and the result is the equivalent of felt banners in various media. For those committees with the wisdom and faith to trust their vision to skilled professionals, they must balance risk with benefits. Of course, commissioning the small scale or seasonal is less risky than the monumental or site-specific. Trendy vestments and metalware that have seen their day can be moth-balled in the far corner of the sacristy closet with little notice, freestanding statues can be moved to other locations in the future, but life-size mosaics or stained glass windows will either be enjoyed or endured by generations of worshipers. The larger or more permanent the piece, the more confident patron and artist must be in its planning and execution.

Some forms of religious art are more regimented that others. Iconographer Czarnecki likens the parameters of his orthodox art form to playing classical music and finds relief in the lack of originality, allowing him to carry on a tradition and concentrate on perfecting his craft. At the other end of the spectrum, our own Ronald Neill Dixon will sometimes challenge a committee, if only in an effort to avoid repeating himself after decades of designing. Amidst a commission for 24 scenic stained glass windows of the life of Christ, his composition for the Ascension window created much consternation with its awe-struck angel and deep red tones. "If you don’t like it, I’ll take it out and make a new window any way you like," he promised. Post-installation, the consternation turned to compliments, including one from a priest and former art professor who appreciated the fresh take and said he could "hear the power of that moment in the window."

Time & Money

Once the process has been entrusted to the artist for fabrication, the committee members become anxious about the schedule. "How long will it take to make?" they always ask. "Not as long as it took you to decide" is the imagined response of many a meeting-weary artist. Photos, progress reports, online updates, even an occasional visit to the studio can alleviate some apprehension. But the visual arts are not performance art and the committee should trust themselves to have chosen well, and in turn to trust their artist to execute their vision.

Both client and creator need to be realistic about cost and payments. The commodity here is originality, uniqueness; there is no amortization of costs incurred in the design process to achieve a low cost per unit in large quantities, nor does it make sense to design a one-of-a-kind piece and execute it in cheap materials. Although artists cannot be expected to bid against mass production, they should be able to justify the cost and value of their creations, and they should offer a written contract or purchase order which notes schedule, a fixed cost, and progressive payments due at measurable intervals such as purchase of materials, completion of shop drawings, completion of fabrication and installation.

The religious artist’s business plan consists of original designs crafted of the finest materials and sold to a charity. While this may seem unrealistic, careers and firms have been sustained on this model –and a belief in miracles. Just as counter-intuitive and effective is the fact that spending on the exquisite can create a surplus to fund the commonplace. Indeed, individuals who would ignore a generic capital campaign can be motivated to give to beautification efforts whether communal or memorial opportunities. Thus, sponsorship of artwork is often offered over cost to parishioners who will cheerfully underwrite building and maintenance costs along with creating an inspiring worship environment.

The Master Plan

"Maybe we should not be in such a rush to have our churches finished," says Fr. John Valencheck, who laments the practice of so-called art being purchased out of catalogues in order to minimize time and cost involved and to have everything in place on dedication day. Although it is beyond the means of many religious communities to commission original art and furnishings while also constructing a building, a long term wish list is a wise investment. Thus, as funds become available, through church growth or individual gifts and legacies, they can be spent on elements that will layer over time to complete a unified vision.

Each commission is a journey from an abstract idea to a tangible creation. Some journeys take longer than others, some are to exotic destinations while others will stay in familiar territory. As every successful journey allows us to see the world and ourselves from a different perspective, so too an excursion into the arts can offer fresh insight to one’s faith.

This article appeared in the national ecumenical magazine, Faith & Form, in 2013.

Images, used w/permission:

mosaic in progress, Dixon Studio

completed icon, Marek Czarnecki

tapestry in progress, Dixon Studio

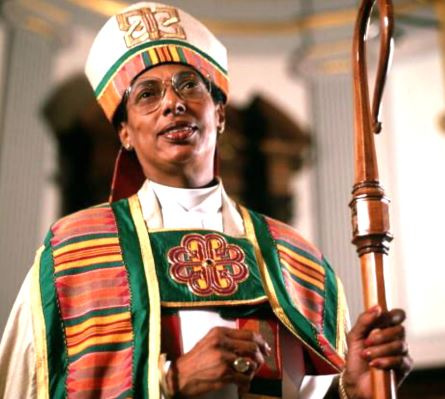

completed vestments, Challwood Studio

stained glass installation, Dixon Studio

For more articles by Annie Dixon, click here